Migrant,

Refugee, Other: How does the BBC portray refugees in three media products?

Introduction

One month ago, October 27th, 2020, a boat crossing the English Channel from France capsized, killing four refugees with at least fifteen others taken to hospital (Williamson 2020). This incident is tragic, but not isolated – it’s just one of the many cases we’ve been exposed to in the overreported refugee ‘crisis’[1]. The media have reported the subject in such a way that certain images are likely to spring to mind when prompted by the word migrant, refugee or asylum seeker. Despite these common portrayals in the media, how much do we actually know about these individuals that risk, and sometimes lose, their lives reaching for Europe?

The way this ‘crisis’ is covered is important. It is the basis on which the majority will form their perceptions and opinions on refugees. The news, documentaries, newspapers, TV programmes and films create and perpetuate stereotypes associated with refugees. This essay will focus on three specific examples of media products from the BBC; BBC Breakfast Show’s live news coverage from August 2020, a BBC Panorama documentary Coronavirus Crisis: Europe’s Migrant Camps, and an episode of BBC Three’s TV Series The Insider: Reggie Yates – In a Refugee Camp. These products were selected for their distinct formats from a common channel whose mission is ‘to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain’ (BBC 2020).

Discussion will focus on the depiction of refugees in each of the three media products with the aim of answering three key research questions;

RQ1) What does this product bring to the wider conversation on refugees?

RQ2) What impact does this have on public perception?

RQ3) To what extent does the format dictate what is shown?

As noted in Ofcom’s Annual Report, ‘the BBC is the most-used news source in the UK and has an important role to play in informing the nation’ (Ofcom 2020, 6). Therefore, it is interesting to explore whether, and if so how, the BBC does this in this small sample of audio-visual products and whether their representations corroborate each other and the general media narrative.

Theoretical Framework

In 2015, ‘journalists reported the biggest mass movement of people around the world in recent history’ with everyday seeming ‘to bring a new migration tragedy’ (Cook & White 2015, 5). Generally, this movement continues to be reported and framed in several dominant ways by the media and humanitarian groups. Fuyuki Kurasawa describes a framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’ which comprises four main typification’s, namely – personification, massification, care and rescue. He describes how these four areas are ‘a set of narratively and visually based mechanisms aiming to trigger feelings of sympathy, repugnance, pity, and nobleness amongst northern audiences toward subjects represented as victims’ (Kurasawa 2013, 202). The characteristics of each typification varies, with personification consisting of close-up shots of single or small groups of victims to underscore their vulnerability and intensify their suffering but done so in a ‘decontextualized manner that depicts him or her as an isolated figure cut off from other actors as well as his or her surroundings’ (op.cit., 207). On the other hand, massification is composed of large groups of bodies close together on boats or in camps with the purpose of showing sheer magnitude, subsequently generating a feeling of repugnance in viewers because of ‘dehumanising effects of ‘piling up’’ (ibid.). Massification simultaneously encourages fear through a framing of threat, magnifying the distance between ‘us’ and the faceless ‘them’. The third typification, rescue, reinforces this tired trope of the white westerner transcending ‘the deadly or unjust circumstances’ to rescue the poor non-westerner of colour who is helpless, vulnerable and stripped of agency (op.cit., 208). Finally, care is ‘structured around an intersubjective and interpersonal relationship between aid and workers and the victims’ (ibid.) evoking a sympathetic response in viewers who may well believe that their capacity to react compassionately denotes their morally elevated status as caring persons and concerned subjects’ (op.cit., 209). Therefore, through Kurasawa’s framework ‘it can be identified what key aspects can contribute to how refugees are imagined in the minds of Western audiences, and how these notions influence strong (and mostly negative) public opinion’ (Lenette 2017, 16).

Live News Coverage

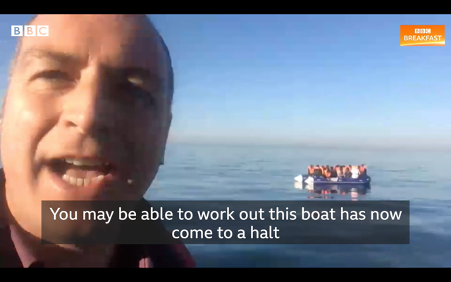

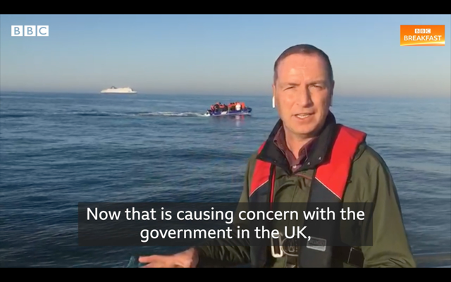

Using Kurasawa’s framework we can turn our focus to the first product, the BBC Breakfast Show’s live coverage of refugees in August 2020. Over the course of several mornings, the BBC reported live from Dover where the reporter, Simon Jones, was in the Channel commentating on dinghies they’d spotted coming from France. This coverage was accused of voyeurism (The Guardian 2020). There were several moments of this coverage when the refugees were struggling. ‘This boat has come to a halt because the engine has broken down’ (BBC Breakfast 2020), Jones says in quite a matter-of-fact manner, ‘they’re using a plastic container just to try to bail out the boat, so obviously it’s pretty overloaded’ (@BBCBreakfast 2020). Capturing these moments is sensationalist. It’s not impartial, high-quality or informative. It is inhuman to watch people’s moments of desperation and exaggerates their ‘otherness’ to viewers.

![]()

(BBC Breakfast 2020)

With such a vast viewership, the BBC Breakfast Show footage is likely to impact people’s attitudes towards refugees. As such this hackneyed and stereotypical framing in the form of massification and threat is detrimental. This portrayal of overcrowded dinghies feeds into the narrative that there is ‘a seemingly endless tide of people’ coming to ‘steal jobs, become a burden on the state and ultimately threaten the native way of life’ (Cook & White 2015, 7). The coverage fails to reveal any truth about the origins and lives of refugees and therefore falls within Kurasawa’s second typification. Given the brief slot allocated to live news reports, there isn’t time to delve into the history of the refugees. However, if the reporter has a moment to comment upon the politics of the country the refugees are destined to, for example, that their arrival is ‘causing concern with the government in the UK, they’re saying the French need to toughen up’ (BBC Breakfast 2020), then perhaps there’s a moment to acknowledge the conditions they are fleeing from. According to Ethical Journalism Network’s Ethical Guidelines on Migration Reporting, there are five key points reporting should follow, namely, facts not bias, know the law, show humanity, speak for all and challenge hate (Ethical Journalism Network). This example of refugee coverage does not adhere to several of these, notably the lack of humanity and lack of voice, but overall, this is not responsible or objective coverage expected from the BBC.

![]()

(BBC Breakfast 2020)

Panorama Documentary

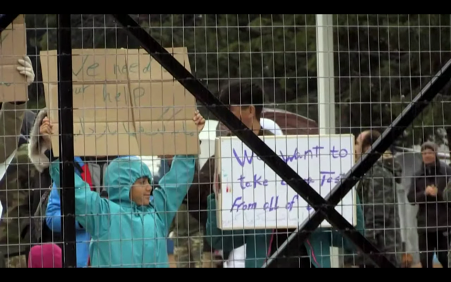

In general, media coverage, like the BBC Breakfast Show, dehumanises refugees by denying them a voice. Shouting over to the parallel dinghy, ‘ARE YOU ALRIGHT? WHERE ARE YOU FROM? […] WHERE ARE YOU GOING?’ (@BBCBreakfast 2020), does not count as an interview and does nothing more than turn refugee experience into a spectacle. However, though opportunities might be few and far between, refugees’ voices can be heard, as they are in BBC Panorama’s investigative documentary Coronavirus Crisis: Europe’s Migrant Camps. Like the news, documentaries are expected to inform and educate, to ‘tell a true story, often from a particular perspective’ trying to ‘elicit a feeling of what the real event’ was like, with audiences expecting little modifications (Maccarone 2010, 195). Since reporters were not able to enter refugee camps in Greece due to the pandemic, Reza, an Afghan journalist, news reporter and refugee explains first-hand what lockdown looks like in Malakasa camp near Athens. Reza’s report, along with other refugees who contributed accounts from their differing camps, is devastating and evokes strong feelings of sympathy in audiences. This is down to the tone and delivery. Unlike the news, in this documentary the narrators explaining the suffering in the camps experience the same suffering. This is audible through the emotion in their voices, ‘the tents are wet, and these innocent children are like this, I don’t know, oh my god. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ (BBCPanorama 2020) says Reza when he finds some families whose tents are surrounded and soaked in water.

![]()

(BBCPanorama 2020)

In many ways, this documentary counters Kurasawa’s framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’, because although it may objectively personify and massify the refugees through the shots that are used, it goes deeper contextually by either the narrator of each refugee camp explaining the current situations, or by the narrator asking questions to others. This representation is far more humanising. It counters the stereotype that refugees are threatening or passive bodies without agency, showing the western audience that, just like them, refugees have voices, use mobile phones, and worry about the health of their loved ones during a pandemic. Furthermore, we see the rescue typification challenged, as ‘victims’ protest against the UN representatives in charge of their camps who have failed to deliver food. Therefore, instead of seeing ‘a scene of rescue’ with ‘aid workers in the process of saving the lives of victims of conflict, starvation, or servitude’ (Kurasawa 2013, 208) we see the rescuers contributing to their suffering.

![]()

(BBCPanorama 2020)

Episode of The Insider

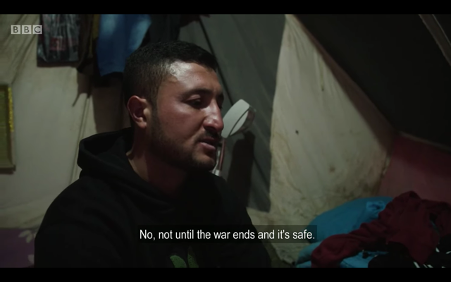

Though the episode of The Insider: Reggie Yates – In a Refugee Camp evokes pity, it takes a softer approach in order to entertain its audience. Aired on BBC Three, an online only channel and hosted by TV personality, Reggie Yates, it attracts a different kind of viewership. Reggie goes ‘through the process’ of seeking refugee status and spends a week living in Domiz, the largest refugee camp in Iraq, ‘to try and find out what life is like for those left behind’ (Redddocs 2017). From the get-go, the tone is far more light-hearted than the previous two media products, with sound effects more reminiscent of a game show than a factual programme, Reggie claims he doesn’t know how he’s going to survive. Prioritising entertainment at the expense of human suffering is ‘poverty porn: a label that acknowledges the prurient and voyeuristic nature of such programming as well as the objectification of its subjects’ (Feltwell, Vines, Salt, et al 2017, 345). With his camera crew by his side, he has the privilege to call the process of claiming asylum ‘laborious’ (Redddocs 2017), an insensitive conclusion to draw. Reggie continues to make patronising remarks throughout the episode, ‘you’re a proper modern woman’ (ibid.), he says, congratulating Fatima for practising yoga. Comments like these highlights both western ignorance and the digestibility of the show.

![]()

(Redddocs 2017)

Reggie represents the celebrity figure ‘by physically enacting such dispositions of compassionate care, celebrity visualities act as metonymies of empathetic publics at large, inviting ‘us’ to engage with those excluded at Europe’s borders’ (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, 10). For the vast majority of the audience watching this, the concept of a refugee camp is something so foreign to them, so placing a recognisable face who draws some comparisons between the people in the camp to themselves does allow them to confront the issue a little more. In terms of Kurasawa’s framework, this media falls within the typification of care in the sense that, like the aid worker, Reggie is the vessel through which the audience learns to care and feel compassion for the refugees, subsequently elevating their sense of nobleness. While the episode is more focused on whether Reggie can endure the week, it does bridge some distance between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Giving some refugees a chance to speak and tell their stories is, as previously discussed, an insight which is not usually shared. However, the difference between this and the Panorama documentary is that while the refugees are given attention, ‘they are not the ones in control of it’ (ibid.).

![]()

(Redddocs 2017)

Interestingly, this is the only media of the three that refers to the refugees as refugees and not migrants. UK media tends to prioritise using migrant, however, according to the UNHCR, migrants are persons who ‘choose to move not because of a direct threat of persecution or death, but mainly to improve their lives’ (Edwards 2016). Alternatively, ‘refugees are persons fleeing armed conflict or persecution’ (ibid.) and this episode backs up this use of terminology at the end when Reggie acknowledges how the people in the camp are stuck and cannot go home. Though the conflation between migrant and refugee might seem slight, its implications are detrimental to the needs of refugees and the public opinion of them, used to fuel the xenophobic narratives of job stealing and benefit scrounging. It is also the media of the three that gives most depth into the critical conditions the refugees have fled from, in this case in Syria, the journeys people underwent to reach Domiz and the opportunities for their future.

![]()

(Redddocs 2017)

Overall, Reggie paints a rather rosy scene of life in Domiz. Caroline Lenette notes that ‘it is fairly unusual to come across visual depictions of refugee camps, in particular, that convey more positive aspects linked to resilience, livelihood, and community’ (Lenette 2017, 3). This episode shows how Domiz has turned, much to Reggie’s surprise, into somewhere which he describes as resembling a major city with restaurants, phone shops, bakeries, hospitals, but most importantly a community spirit. This is the journey Reggie has embarked on. He enters Domiz naïve, bearing the perception that if people are building houses and community they have given up, but leaves six days later having survived and shaken this conception, replacing it with the realisation that people are ‘just making the most of a terrible situation’ (Redddocs 2017).

Conclusion

Kurasawa’s framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’ has been useful to identify whether these examples are typical representations of refugees, through which we have learnt that the BBC does not portray refugees consistently across these products. In some cases, the representation is in line with the general stereotypical media narrative, while in others it diverges. Therefore, the BBC does not wholeheartedly commit to its mission statement, dropping the ball regarding impartiality in particular when we think about the Breakfast Show coverage but,RQ3) To what extent does the format dictate what is shown? In general, the brevity of live news format does hinder its performance as an informative, well thought out piece. Deep contextual information is neither present nor expected, but refugees could be given more verbal and visual consideration. If boiled down, this news coverage was less about refugees and more about policies and politics. If it were about the refugees, we should have heard something about their plight and their history, instead of how French and UK officials are pointing the finger at one another. The ‘crisis’ here is a sensationalist scene portrayed ‘as a humanitarian ‘emergency’ rather than as a failure of international politics’ (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, 7). Alternatively, the other two products had the luxuries of time and editing in order to flesh out their representations. Considering these two aspects, and the access Reggie and his camera crew were permitted, The Insider could have been a really informative piece. However, the chosen format of celebrity survival show reduces its credibility. Though this specific Panorama documentary was more focused on the effects of the pandemic in Greek refugee camps, this format that gives refugee voices a platform, could be an effective and informative model. In doing so, it challenges the perception audiences are generally led to have by mass media, suggesting that more journalists who are refugees should be given a platform as their accounts get ‘closer to the story and its roots’ (Suffee 2015, 43).

This closeness allows space for a different conversation on refugees in comparison to the stereotypical. In regards to, RQ1) What does this product bring to the wider conversation on refugees?, the Panorama documentary does not shy away from the harsh realities of living in a refugee camp. While some refugees have decent living conditions, others live in waterlogged tents submerged in their poverty and Reza is vocal about how scarce amenities and services are, particularly during the pandemic. By hearing directly from refugees, it shows that they are human though living in inhuman circumstances. This generates a level of empathy through both our shared experience of COVID-19 and by witnessing the reality of camps. Though being places of refuge, we learn how being in this camp comes hand in hand with desperation and violence, information that could lead audiences to wider discussions of action or simply oh dear-ism. Although using a different tone, The Insider also brings the refugees humanity to the wider discussion. By showing how the refugees come and go from the camp to work in nearby towns, get married, make choices and form a community we learn they are more than mere bodies. The representation of refugees in this episode is not perfect but we see how they have agency, while simultaneously being limited by the fact they are refugees, as Reggie says, ‘the majority of people I’ve met here are stuck with no end in sight’ (Redddocs 2017). As discussed, Reggie represents the caring celebrity, keen to lend a hand, however, quite the opposite is true of the Breakfast Show news. Though we should acknowledge it is not the reporter’s duty to stop and help, it raises the question of whether this type of coverage is necessary. Of course, we should have coverage about refugees but what positives derive from cases like these?

Coverage like the BBC Breakfast Show’s perpetuates stereotypes, so, RQ2) What impact does this have on public perception? As discussed, the visual representation of refugees has become the most translatable knowledge about them (Malkki 1996) and therefore, the publics take home of these morning segments are those feelings of threat and/or repugnance which were likely already engrained. By combining the refugees with the politics of their arrival is problematising rather than humanising, feeding into the mentality of ‘crisis’. Although, giving a more humanising image of refugees, The Insider allows the audience to brush over issues such as gender-based violence (UN Women 2014) and poor mental health (Wood 2014) which are rife in the camp, subsequently depriving them of the full picture. If the BBC Three audience began watching with the same level of naivety as Reggie when he entered, then the viewer will have learnt that refugees are also 21st century people with hopes similar to their own. While this episode does some good, its tongue and cheek approach does some harm. Reggie acknowledges how ‘it’s not an easy life here’ (Redddocs 2017) but shows a fairly light-hearted account of life in Domiz. While giving airtime to some hardships, such as losing or leaving family, the episode doesn’t dig too much and glosses over some of the realities in a way which Panorama does not. What this documentary exemplifies is that ‘in order to show the humanity of the suffering other, more than victimhood needs to be represented’ (Hiltunen 2019, 153) and having Reza, amongst other refugees, share their accounts on a personal and human level allows the public to connect in a more genuine way.

[1] Crisis is in adverted commas because of misuse of the word. This word is generally used to refer to the refugees being the crisis, but actually what they are fleeing from is crisis.

Introduction

One month ago, October 27th, 2020, a boat crossing the English Channel from France capsized, killing four refugees with at least fifteen others taken to hospital (Williamson 2020). This incident is tragic, but not isolated – it’s just one of the many cases we’ve been exposed to in the overreported refugee ‘crisis’[1]. The media have reported the subject in such a way that certain images are likely to spring to mind when prompted by the word migrant, refugee or asylum seeker. Despite these common portrayals in the media, how much do we actually know about these individuals that risk, and sometimes lose, their lives reaching for Europe?

The way this ‘crisis’ is covered is important. It is the basis on which the majority will form their perceptions and opinions on refugees. The news, documentaries, newspapers, TV programmes and films create and perpetuate stereotypes associated with refugees. This essay will focus on three specific examples of media products from the BBC; BBC Breakfast Show’s live news coverage from August 2020, a BBC Panorama documentary Coronavirus Crisis: Europe’s Migrant Camps, and an episode of BBC Three’s TV Series The Insider: Reggie Yates – In a Refugee Camp. These products were selected for their distinct formats from a common channel whose mission is ‘to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain’ (BBC 2020).

Discussion will focus on the depiction of refugees in each of the three media products with the aim of answering three key research questions;

RQ1) What does this product bring to the wider conversation on refugees?

RQ2) What impact does this have on public perception?

RQ3) To what extent does the format dictate what is shown?

As noted in Ofcom’s Annual Report, ‘the BBC is the most-used news source in the UK and has an important role to play in informing the nation’ (Ofcom 2020, 6). Therefore, it is interesting to explore whether, and if so how, the BBC does this in this small sample of audio-visual products and whether their representations corroborate each other and the general media narrative.

Theoretical Framework

In 2015, ‘journalists reported the biggest mass movement of people around the world in recent history’ with everyday seeming ‘to bring a new migration tragedy’ (Cook & White 2015, 5). Generally, this movement continues to be reported and framed in several dominant ways by the media and humanitarian groups. Fuyuki Kurasawa describes a framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’ which comprises four main typification’s, namely – personification, massification, care and rescue. He describes how these four areas are ‘a set of narratively and visually based mechanisms aiming to trigger feelings of sympathy, repugnance, pity, and nobleness amongst northern audiences toward subjects represented as victims’ (Kurasawa 2013, 202). The characteristics of each typification varies, with personification consisting of close-up shots of single or small groups of victims to underscore their vulnerability and intensify their suffering but done so in a ‘decontextualized manner that depicts him or her as an isolated figure cut off from other actors as well as his or her surroundings’ (op.cit., 207). On the other hand, massification is composed of large groups of bodies close together on boats or in camps with the purpose of showing sheer magnitude, subsequently generating a feeling of repugnance in viewers because of ‘dehumanising effects of ‘piling up’’ (ibid.). Massification simultaneously encourages fear through a framing of threat, magnifying the distance between ‘us’ and the faceless ‘them’. The third typification, rescue, reinforces this tired trope of the white westerner transcending ‘the deadly or unjust circumstances’ to rescue the poor non-westerner of colour who is helpless, vulnerable and stripped of agency (op.cit., 208). Finally, care is ‘structured around an intersubjective and interpersonal relationship between aid and workers and the victims’ (ibid.) evoking a sympathetic response in viewers who may well believe that their capacity to react compassionately denotes their morally elevated status as caring persons and concerned subjects’ (op.cit., 209). Therefore, through Kurasawa’s framework ‘it can be identified what key aspects can contribute to how refugees are imagined in the minds of Western audiences, and how these notions influence strong (and mostly negative) public opinion’ (Lenette 2017, 16).

Live News Coverage

Using Kurasawa’s framework we can turn our focus to the first product, the BBC Breakfast Show’s live coverage of refugees in August 2020. Over the course of several mornings, the BBC reported live from Dover where the reporter, Simon Jones, was in the Channel commentating on dinghies they’d spotted coming from France. This coverage was accused of voyeurism (The Guardian 2020). There were several moments of this coverage when the refugees were struggling. ‘This boat has come to a halt because the engine has broken down’ (BBC Breakfast 2020), Jones says in quite a matter-of-fact manner, ‘they’re using a plastic container just to try to bail out the boat, so obviously it’s pretty overloaded’ (@BBCBreakfast 2020). Capturing these moments is sensationalist. It’s not impartial, high-quality or informative. It is inhuman to watch people’s moments of desperation and exaggerates their ‘otherness’ to viewers.

(BBC Breakfast 2020)

With such a vast viewership, the BBC Breakfast Show footage is likely to impact people’s attitudes towards refugees. As such this hackneyed and stereotypical framing in the form of massification and threat is detrimental. This portrayal of overcrowded dinghies feeds into the narrative that there is ‘a seemingly endless tide of people’ coming to ‘steal jobs, become a burden on the state and ultimately threaten the native way of life’ (Cook & White 2015, 7). The coverage fails to reveal any truth about the origins and lives of refugees and therefore falls within Kurasawa’s second typification. Given the brief slot allocated to live news reports, there isn’t time to delve into the history of the refugees. However, if the reporter has a moment to comment upon the politics of the country the refugees are destined to, for example, that their arrival is ‘causing concern with the government in the UK, they’re saying the French need to toughen up’ (BBC Breakfast 2020), then perhaps there’s a moment to acknowledge the conditions they are fleeing from. According to Ethical Journalism Network’s Ethical Guidelines on Migration Reporting, there are five key points reporting should follow, namely, facts not bias, know the law, show humanity, speak for all and challenge hate (Ethical Journalism Network). This example of refugee coverage does not adhere to several of these, notably the lack of humanity and lack of voice, but overall, this is not responsible or objective coverage expected from the BBC.

(BBC Breakfast 2020)

Panorama Documentary

In general, media coverage, like the BBC Breakfast Show, dehumanises refugees by denying them a voice. Shouting over to the parallel dinghy, ‘ARE YOU ALRIGHT? WHERE ARE YOU FROM? […] WHERE ARE YOU GOING?’ (@BBCBreakfast 2020), does not count as an interview and does nothing more than turn refugee experience into a spectacle. However, though opportunities might be few and far between, refugees’ voices can be heard, as they are in BBC Panorama’s investigative documentary Coronavirus Crisis: Europe’s Migrant Camps. Like the news, documentaries are expected to inform and educate, to ‘tell a true story, often from a particular perspective’ trying to ‘elicit a feeling of what the real event’ was like, with audiences expecting little modifications (Maccarone 2010, 195). Since reporters were not able to enter refugee camps in Greece due to the pandemic, Reza, an Afghan journalist, news reporter and refugee explains first-hand what lockdown looks like in Malakasa camp near Athens. Reza’s report, along with other refugees who contributed accounts from their differing camps, is devastating and evokes strong feelings of sympathy in audiences. This is down to the tone and delivery. Unlike the news, in this documentary the narrators explaining the suffering in the camps experience the same suffering. This is audible through the emotion in their voices, ‘the tents are wet, and these innocent children are like this, I don’t know, oh my god. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ (BBCPanorama 2020) says Reza when he finds some families whose tents are surrounded and soaked in water.

(BBCPanorama 2020)

In many ways, this documentary counters Kurasawa’s framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’, because although it may objectively personify and massify the refugees through the shots that are used, it goes deeper contextually by either the narrator of each refugee camp explaining the current situations, or by the narrator asking questions to others. This representation is far more humanising. It counters the stereotype that refugees are threatening or passive bodies without agency, showing the western audience that, just like them, refugees have voices, use mobile phones, and worry about the health of their loved ones during a pandemic. Furthermore, we see the rescue typification challenged, as ‘victims’ protest against the UN representatives in charge of their camps who have failed to deliver food. Therefore, instead of seeing ‘a scene of rescue’ with ‘aid workers in the process of saving the lives of victims of conflict, starvation, or servitude’ (Kurasawa 2013, 208) we see the rescuers contributing to their suffering.

(BBCPanorama 2020)

Episode of The Insider

Though the episode of The Insider: Reggie Yates – In a Refugee Camp evokes pity, it takes a softer approach in order to entertain its audience. Aired on BBC Three, an online only channel and hosted by TV personality, Reggie Yates, it attracts a different kind of viewership. Reggie goes ‘through the process’ of seeking refugee status and spends a week living in Domiz, the largest refugee camp in Iraq, ‘to try and find out what life is like for those left behind’ (Redddocs 2017). From the get-go, the tone is far more light-hearted than the previous two media products, with sound effects more reminiscent of a game show than a factual programme, Reggie claims he doesn’t know how he’s going to survive. Prioritising entertainment at the expense of human suffering is ‘poverty porn: a label that acknowledges the prurient and voyeuristic nature of such programming as well as the objectification of its subjects’ (Feltwell, Vines, Salt, et al 2017, 345). With his camera crew by his side, he has the privilege to call the process of claiming asylum ‘laborious’ (Redddocs 2017), an insensitive conclusion to draw. Reggie continues to make patronising remarks throughout the episode, ‘you’re a proper modern woman’ (ibid.), he says, congratulating Fatima for practising yoga. Comments like these highlights both western ignorance and the digestibility of the show.

(Redddocs 2017)

Reggie represents the celebrity figure ‘by physically enacting such dispositions of compassionate care, celebrity visualities act as metonymies of empathetic publics at large, inviting ‘us’ to engage with those excluded at Europe’s borders’ (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, 10). For the vast majority of the audience watching this, the concept of a refugee camp is something so foreign to them, so placing a recognisable face who draws some comparisons between the people in the camp to themselves does allow them to confront the issue a little more. In terms of Kurasawa’s framework, this media falls within the typification of care in the sense that, like the aid worker, Reggie is the vessel through which the audience learns to care and feel compassion for the refugees, subsequently elevating their sense of nobleness. While the episode is more focused on whether Reggie can endure the week, it does bridge some distance between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Giving some refugees a chance to speak and tell their stories is, as previously discussed, an insight which is not usually shared. However, the difference between this and the Panorama documentary is that while the refugees are given attention, ‘they are not the ones in control of it’ (ibid.).

(Redddocs 2017)

Interestingly, this is the only media of the three that refers to the refugees as refugees and not migrants. UK media tends to prioritise using migrant, however, according to the UNHCR, migrants are persons who ‘choose to move not because of a direct threat of persecution or death, but mainly to improve their lives’ (Edwards 2016). Alternatively, ‘refugees are persons fleeing armed conflict or persecution’ (ibid.) and this episode backs up this use of terminology at the end when Reggie acknowledges how the people in the camp are stuck and cannot go home. Though the conflation between migrant and refugee might seem slight, its implications are detrimental to the needs of refugees and the public opinion of them, used to fuel the xenophobic narratives of job stealing and benefit scrounging. It is also the media of the three that gives most depth into the critical conditions the refugees have fled from, in this case in Syria, the journeys people underwent to reach Domiz and the opportunities for their future.

(Redddocs 2017)

Overall, Reggie paints a rather rosy scene of life in Domiz. Caroline Lenette notes that ‘it is fairly unusual to come across visual depictions of refugee camps, in particular, that convey more positive aspects linked to resilience, livelihood, and community’ (Lenette 2017, 3). This episode shows how Domiz has turned, much to Reggie’s surprise, into somewhere which he describes as resembling a major city with restaurants, phone shops, bakeries, hospitals, but most importantly a community spirit. This is the journey Reggie has embarked on. He enters Domiz naïve, bearing the perception that if people are building houses and community they have given up, but leaves six days later having survived and shaken this conception, replacing it with the realisation that people are ‘just making the most of a terrible situation’ (Redddocs 2017).

Conclusion

Kurasawa’s framework of ‘humanitarian sentimentalism’ has been useful to identify whether these examples are typical representations of refugees, through which we have learnt that the BBC does not portray refugees consistently across these products. In some cases, the representation is in line with the general stereotypical media narrative, while in others it diverges. Therefore, the BBC does not wholeheartedly commit to its mission statement, dropping the ball regarding impartiality in particular when we think about the Breakfast Show coverage but,RQ3) To what extent does the format dictate what is shown? In general, the brevity of live news format does hinder its performance as an informative, well thought out piece. Deep contextual information is neither present nor expected, but refugees could be given more verbal and visual consideration. If boiled down, this news coverage was less about refugees and more about policies and politics. If it were about the refugees, we should have heard something about their plight and their history, instead of how French and UK officials are pointing the finger at one another. The ‘crisis’ here is a sensationalist scene portrayed ‘as a humanitarian ‘emergency’ rather than as a failure of international politics’ (Chouliaraki & Stolic 2017, 7). Alternatively, the other two products had the luxuries of time and editing in order to flesh out their representations. Considering these two aspects, and the access Reggie and his camera crew were permitted, The Insider could have been a really informative piece. However, the chosen format of celebrity survival show reduces its credibility. Though this specific Panorama documentary was more focused on the effects of the pandemic in Greek refugee camps, this format that gives refugee voices a platform, could be an effective and informative model. In doing so, it challenges the perception audiences are generally led to have by mass media, suggesting that more journalists who are refugees should be given a platform as their accounts get ‘closer to the story and its roots’ (Suffee 2015, 43).

This closeness allows space for a different conversation on refugees in comparison to the stereotypical. In regards to, RQ1) What does this product bring to the wider conversation on refugees?, the Panorama documentary does not shy away from the harsh realities of living in a refugee camp. While some refugees have decent living conditions, others live in waterlogged tents submerged in their poverty and Reza is vocal about how scarce amenities and services are, particularly during the pandemic. By hearing directly from refugees, it shows that they are human though living in inhuman circumstances. This generates a level of empathy through both our shared experience of COVID-19 and by witnessing the reality of camps. Though being places of refuge, we learn how being in this camp comes hand in hand with desperation and violence, information that could lead audiences to wider discussions of action or simply oh dear-ism. Although using a different tone, The Insider also brings the refugees humanity to the wider discussion. By showing how the refugees come and go from the camp to work in nearby towns, get married, make choices and form a community we learn they are more than mere bodies. The representation of refugees in this episode is not perfect but we see how they have agency, while simultaneously being limited by the fact they are refugees, as Reggie says, ‘the majority of people I’ve met here are stuck with no end in sight’ (Redddocs 2017). As discussed, Reggie represents the caring celebrity, keen to lend a hand, however, quite the opposite is true of the Breakfast Show news. Though we should acknowledge it is not the reporter’s duty to stop and help, it raises the question of whether this type of coverage is necessary. Of course, we should have coverage about refugees but what positives derive from cases like these?

Coverage like the BBC Breakfast Show’s perpetuates stereotypes, so, RQ2) What impact does this have on public perception? As discussed, the visual representation of refugees has become the most translatable knowledge about them (Malkki 1996) and therefore, the publics take home of these morning segments are those feelings of threat and/or repugnance which were likely already engrained. By combining the refugees with the politics of their arrival is problematising rather than humanising, feeding into the mentality of ‘crisis’. Although, giving a more humanising image of refugees, The Insider allows the audience to brush over issues such as gender-based violence (UN Women 2014) and poor mental health (Wood 2014) which are rife in the camp, subsequently depriving them of the full picture. If the BBC Three audience began watching with the same level of naivety as Reggie when he entered, then the viewer will have learnt that refugees are also 21st century people with hopes similar to their own. While this episode does some good, its tongue and cheek approach does some harm. Reggie acknowledges how ‘it’s not an easy life here’ (Redddocs 2017) but shows a fairly light-hearted account of life in Domiz. While giving airtime to some hardships, such as losing or leaving family, the episode doesn’t dig too much and glosses over some of the realities in a way which Panorama does not. What this documentary exemplifies is that ‘in order to show the humanity of the suffering other, more than victimhood needs to be represented’ (Hiltunen 2019, 153) and having Reza, amongst other refugees, share their accounts on a personal and human level allows the public to connect in a more genuine way.

[1] Crisis is in adverted commas because of misuse of the word. This word is generally used to refer to the refugees being the crisis, but actually what they are fleeing from is crisis.